“Autobiography,” a flash story, at Wigleaf:

Now, I live alone in a large house.

Before that, I had a dog named Tobias. He was half pit bull, and my neighbors thought he might be dangerous, but he was the sweetest dog, never bit anyone, not once, not ever. After I hurt my back and couldn't do the things I used to do, he was patient with me, walked right next to my cane, as if he could somehow catch me if I fell.

Before that, the hummingbirds would hover by my feeder every morning to drink the sugar water I'd prepared, and Tobias would watch them through the window, his excited tail thumping the wooden floor. I stood next to him and watched, too, amazed that such tiny birds could exist, that they could propel themselves so quickly with wings that blurred with motion. As we watched the hummingbirds, Tobias would press his warm and solid body into the side of my leg.

“Migration,” a short story, at Story:

Vanessa’s mother’s house is a disaster. There are newspapers—not even real papers, but Pennysavers—piled in the living room, some of them from years ago. “They’re for lining the birdcages,” her mother insists, but the birds are not in the cages, and Vanessa suspects they are never in the cages, which are piled one on top of another, lining an entire wall of the living room. The birds are flying free, squawking, leaving gloopy white messes everywhere. The noise is unbearable, the trills and screeches and chirps, and Vanessa wonders how her mother is able to think with this noise. How many birds are there? Thirty? Forty? Fifty? It feels as if there are a thousand, swooping overhead, landing violently on the mantle, bopping across the dining room table, a small gray one settling on Vanessa’s shoulder. The bird is impervious to Vanessa’s flicking, its tiny, disgusting feet digging deep into her leather jacket. Vanessa peers into the kitchen and sees decades worth of empty Cool Whip containers, which her mother says are for storing leftovers, but when was the last time her mother cooked anything in the filthy kitchen? “Do you have any wine?” Vanessa asks. There must be a glass somewhere in this mess that she can scrub clean before pouring wine into it.

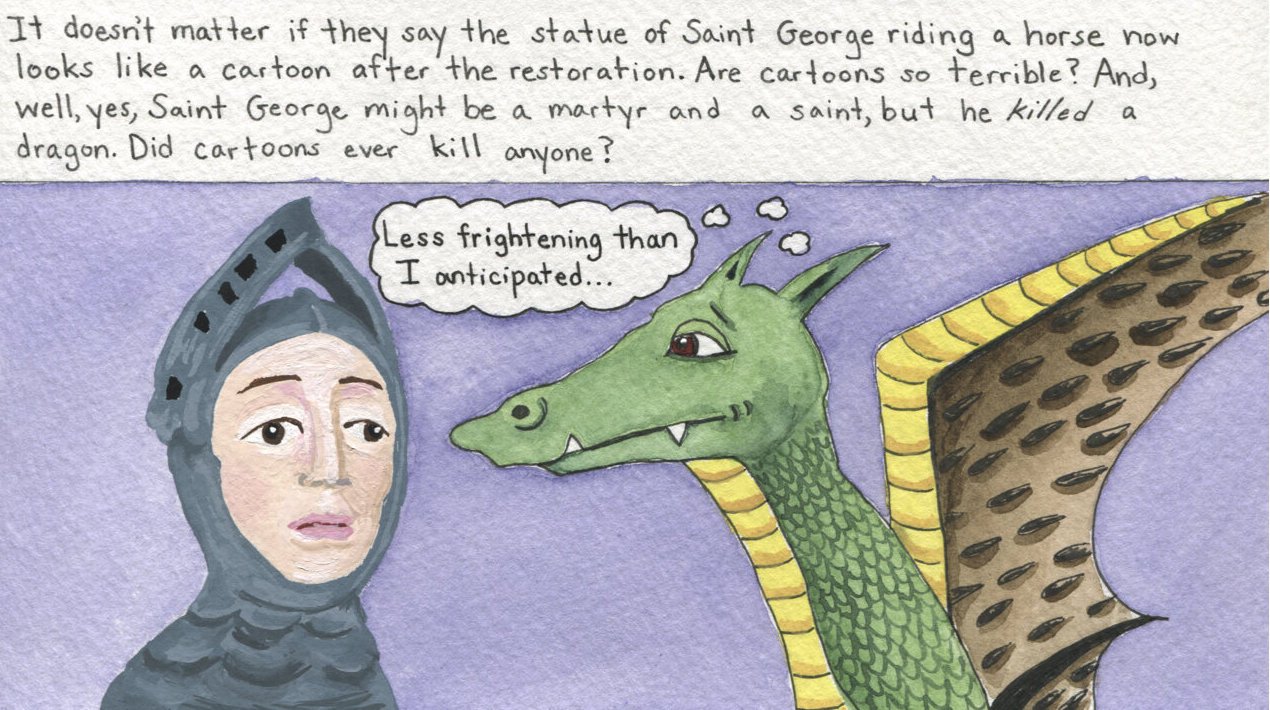

“The Restorers,” a graphic narrative, at Aquifer: The Florida Review Online:

“So Much Trouble,” a short story, winner of CRAFT’s Craft Elements Contest for Characterization:

Katherine had only intended to spend a few minutes outdoors wiping the birdhouse with vegetable oil, but now, over an hour after she’d started, she stood in the front yard, an oil-drenched wad of paper towels in one hand, the slick plastic bottle of oil in the other. Now the lamp pole had been oiled, the drainpipes had been oiled, all the siding she could reach on the front of the house and garage had been oiled, and even the shutters had been oiled. For good measure, she’d also oiled the bark on the tree from which the birdhouse hung, although it was clear that oiling a tree would not make it too slick for a squirrel to climb. But this did not stop Katherine from imagining squirrels sliding down all these surfaces, slipping dramatically, and plunging to the grass. She pictured the squirrels rubbing their sore rears and telling themselves to stay away from Katherine’s property. She imagined them telling their squirrel friends, “It’s dangerous there!” and scampering off to other houses in the neighborhood.

“Unboxing,” a short story, at Memorious:

After Fern exited the mall, she saw Tyler Michaels standing outside of Macy’s swinging a plastic bag from Video Emporium in an arc over his head. Fern had just bought a SpongeBob T-shirt, a birthday present for her friend Carly, and planned to wait outside the mall for her mother to pick her up. Fern and Tyler were both in seventh grade at the same school, but he was popular and she was not, and even though they’d been in several classes together, they’d never spoken directly to each other. If she went back inside the mall, she wouldn’t have to awkwardly stand near Tyler, who might or might not recognize her. But before Fern could go back inside, he called out to her.

“Hey! You go to my school. You have a plant name. Lily? Daisy? Dandelion?”

“It’s Fern.”

“That’s right,” said Tyler. “Are you getting a ride?”

“My mom’s picking me up.”

“My brother was supposed to get me, but he texted and said he entered a pizza eating contest and ate four large pepperoni and sausage pizzas. He needs time to digest before he can drive. Can I have a ride?”

"The Sweeper of Hair," a short story, was a finalist for the Chicago Tribune's Nelson Algren Award:

A year ago the salon was more fun because there were other stylists still working there, and Jackson could talk to them when they weren’t busy cutting or dying or styling hair. There was Irma, with her bright orange hair piled up high on her head, her dangly earrings, her loud laugh that filled the entire salon. There was Missy, who was young and had a small diamond stud in her nose and saw every single movie that came out in the theater in the mall. There was Jack, with his snakeskin boots, who would tease Jackson, saying he was named after him, even though Jackson knows he was named after Michael Jackson, who was his mother’s favorite singer when she was growing up and because he was born on the day Michael Jackson died. But now they are all gone, off to other salons where business is better, and there is a row of empty chairs in the salon, and Jackson’s mother is the only stylist who still works here.

"Swim Test," a flash story, at Shenandoah:

We gather on the last day possible—three days before graduation—for this final requirement, this last hoop to jump through, the one remaining box to check before we receive our degrees. We are lined up in the women’s locker room wearing one-piece swimsuits and flip-flops that have been worn mostly in the dorm showers. Why did we wait so long? What if we fail? There are no more chances after this.

“Touring,” a short story, at Colorado Review:

The parents always love me. I walk backward and wind clumps of parents and their sixteen- and seventeen-year-old offspring through our tree-lined campus and explain why they should spend sixty thousand dollars a year sending their precious progeny to Willton College. I know what they want to hear—our rising ranking in U.S. News & World Report, Princeton Review declaring that our dorms look like palaces, the job and graduate school placement rate, the scholarly successes of our esteemed faculty. Inevitably, some dad, some wannabe comedian in pleated khakis and a tucked-in polo says, “So, what are you going to do with that philosophy degree, Jessica? Will you sit around all day and think?” They chuckle, and their children are mortified. I tell them Willton has provided me with a solid liberal arts education and I have learned to think critically, articulate myself clearly, and write well, and what business or graduate program wouldn’t want someone with these skills?

A Contributor's Spotlight on the Bellingham Review blog about my story "Perspective for Artists" (published here):

Although this piece is about students studying art, it sprang from my contemplation about whether writing can be taught. As someone who makes my living teaching writing (mostly creative writing), I firmly believe students can gain a lot by taking writing classes, studying published work, and learning about craft. I tell my students that they need to learn the rules before they try to break them, but I do stress that rules for writing aren’t necessarily written in stone and there are certainly ways to effectively break rules. Nearly every semester I’ll have a student or two write something in their course evaluations about how they wish they could “just be creative” and write whatever or however they wanted in my class. They don’t see the value in studying, say, how to effectively use dialogue or how to work with conflict in a story, and I was trying to capture this attitude and the desire to “just be creative” in the students in “Perspective For Artists.”

In the summer of 2008, I moved to a small town in Ohio to begin a three-year teaching position at a college. Two of us were hired to start at the same time in the English Department; I was in a visiting position, and my colleague was in a tenure-track position. We sat together at lunch during orientation and began to get to know each other. A tenure-track new hire from the math department slid into the empty seat at our table and spoke only to my colleague, engaging her in conversation about her move to Ohio, her summer, the classes she’d be teaching. He even said—right in front of me—“We’ve got to stick together since we’re both on the tenure track.” I know this sounds like a line of awkward dialogue from a poorly written story, but those words came out of his mouth. As he continued to speak only to my colleague, I realized that he (henceforth to be known as Dr. Math) didn’t allow himself to see me there, that I was—in my visiting position—someone who was essentially invisible to him. I wouldn’t be around for the long haul, and because of this, he didn’t want to invest any time or energy or kindness toward me. Fortunately, most people at the school did not share Dr. Math’s attitude, and I quickly felt that I was part of the community at the college. However, I wondered what it would be like for someone to move to a similar small town and be an outsider not tied to any institution, and that’s where the character of Miller Duskman came from.

“Roland Raccoon,” a short story, at New Ohio Review:

Ms. Gardner had not been in support of the plan to drag Roland Raccoon to every middle school science class, but the principal said they’d paid Margery Martin a flat fee for the school visit, and it would be a waste if every student at Grisham Middle School did not have the opportunity to visit with Roland. Ms. Gardner was certain the eighth graders in her sixth period class were too old to learn life lessons about kindness and compassion and giving everyone and everything a chance from a twelve-year-old blind raccoon that was also deaf in one ear. “But he loves to be sung to,” Margery Martin had informed the class, adding, “in his good ear.” She cradled Roland in her lap as if he were a baby.

Margery leaned down, put her lips unsavorily close to Roland’s ear, and sang something that might have been Frank Sinatra. The boys who were sitting against a bookshelf near the rear of the classroom, as far away from Margery as they were allowed, snickered, and Ms. Gardner heard the word “rabies” whispered several times.

"Perspective For Artists," a short story, at Bellingham Review:

We were the art girls. We had charcoal under our fingernails, flecks of dried clay on our jeans, acrylic paint in our hair. The artsy seniors always lived on the second floor of McAllister Hall; it was tradition. Although our boarding school, Florence Summer Academy for Girls, was beautiful—the dorms looked like magnificent stone castles—McAllister Hall was so run-down inside that they let whoever lived on the second floor paint the walls of their rooms. Each fall, Facilities delivered cans of primer so last year’s walls could be painted over and new masterpieces created.

"Away," a short story at Green Mountains Review:

When the inflatable bouncy castle I’m jumping in with a handful of five-year-olds is lifted off the ground by a gust of wind, I think of my cousin Garnet and her story of being snatched by a hawk. Six years ago, when we were twelve, we were both sent to Camp Spruce in New Hampshire, and it was there that she began to tell lies, starting with the one about the hawk. Our parents requested that we bunk in the same cabin, and I assumed I would be the cool one, the one who knew about pop music and movies and had a stack of Seventeen magazines in my duffel bag, and Garnet would be my loser cousin—a homeschooled girl from Kansas in long skirts and Birkenstocks whose family didn’t even own a television—that I would grudgingly be nice to.

"Care," a story at Kenyon Review Online:

You’re a bus driver now. And tonight is Halloween, which means drunk college students riding the bus to and from parties. Eventually someone will make a mess—vomit, vampire makeup smeared on a window, a can of soda sloshed onto the floor—and it’s your job to clean it up, even though you’ve written numerous lengthy letters to the Transit Authority regarding the fact that you’re a bus driver, not a maid, and someone should be hired to clean the buses.

A guest blog post about patience and publishing:

Much of my childhood seemed to be about waiting. I owned a book called Free Stuff for Kids, and on each page there was information about something—a bumper sticker, a button, a poster—that kids could send away for and get for free in the mail. Corporations usually sponsored these free things, and thee items advertised their products. I didn’t mind the advertisements. I just thought it was fun to write a letter requesting a free button and then, six to eight weeks later, find a button declaring I loved a certain brand of cereal in a padded envelope in my mailbox.

"In the Orchard," a short story at Five Chapters:

In the orchard, Jonas walks cautiously, trying not to step on any fallen apples. His wife walks a few steps in front of him and lists reason after reason for leaving Manhattan and moving upstate. She tells him they can afford to buy the orchard. She stops and points at the country store at the end of a row of Granny Smiths and says, “I could run the store, sell pies and apple cider. I could write my cookbook here. And you could set up a practice in town.”

Jonas shakes his head, but he does it so gently he is unsure if Molly can even detect the movement. He does not like to deny Molly anything, but he needs to tell her no, she cannot have this place. This is not the right place to settle, to raise a family. She is pregnant with their first child, and he knows she is imagining their child racing around this wide expanse of land. She has some fairytale notion of the place, and when she’d seen that this orchard—right here in the town where Jonas had grown up—was for sale, she’d insisted they take a weekend trip up.

“There’s nothing here for us,” Jonas says.